# Analysis of variation within individual COVID-19 samples | 🔥 updated weekly

Last update = May 20

# Live Resources

| usegalaxy.org | usegalaxy.eu | usegalaxy.org.au | usegalaxy.be | usegalaxy.fr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

# What's the point?

The absolute majority of SARS-COV-2 data is in the form of assembled genomic sequences. This is unfortunate because any variation that exists within individual samples is obliterated--converted to the most frequent base--during the assembly process. However, knowing underlying evolutionary dynamics is critical for tracing evolution of the virus as it allows identification of genomic regions under different selective regimes and understanding of its population parameters.

# Outline

In this analysis we check for new data, run single- or paired-end analysis workflows, aggregate the results, combine them with the list produced in the previous days, and finally analyze the complete, up-to-date set of variants using Jupyter. Here is a brief outline with links:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Obtain Illumina read accessions | Generate list of newly released Illumina datasets. Performed daily. |

(opens new window) (opens new window) | If data is paired-end → run PE workflow |

(opens new window) (opens new window) | If data is single-end → run SE workflow |

(opens new window) (opens new window) | Combine results of PE and SE workflow. This is done in a single Galaxy history that is used to aggregate results of all daily runs. |

(opens new window) (opens new window) | Start Jupyter notebook to analyze variants (it can started directly from history linked at the previous step) |

# Obtaining the data

Raw sequencing reads are required to detection of within-sample sequence variants. We update the list of available data daily using the following logic implemented in fetch_sra_acc.sh:

- Fetch accessions from SARS-CoV-2 resource (opens new window), Short Read Archive at NCBI (opens new window), and EBI (opens new window). This is done daily.

- A union of accessions from these three resources is then computed (

union.txt). - Sample metadata is then obtained for all retained accession numbers and saved into

current_metadata.txt. - Metadata is used to split datasets into

current_illumina.txtandcurrent_gridion.txt. - In addition, we fetch all publicly available complete SARS-CoV-2 genomes. These are stored in

genome_accessions.txtandcurrent_complete_ncov_genomes.fasta.

The list of currently analyzed datasets (as of April 28, 2020) is shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1. SARS-CoV-2 Illumina datasets and corresponding analysis histories.

| Date | Galaxy history |

|---|---|

| Beginning of outbreak - March 20, 2020 | Paired End (opens new window) Single End (opens new window) |

| March 25, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| March 26, 2020 | Paired End (opens new window) |

| April 2, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| April 8, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| April 28, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| May 2, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| May 9, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| May 17, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| May 18, 2020 | Paired and Single Ends (opens new window) |

| History for aggregation | (https://usegalaxy.org/u/sars-cov2-bot/h/covid19-variant-aggregation-analysis) |

# How do we call variants?

This section provides background of how we settled on using lofreq as the principal variant caller for this project.

# Calling variants in haploid mixtures is not standardized

The development of modern genomic tools and formats have been driven by large collaborative initiatives such as 1,000 Genomes, GTEx and others. As a result the majority of current variant callers have been originally designed for diploid genomes of human or model organisms where discrete allele frequencies are expected. Bacterial and viral samples are fundamentally different. They are represented by mixtures of multiple haploid genomes where the frequencies of individual variants are continuous. This renders many existing variant calling tools unsuitable for microbial and viral studies unless one is looking for fixed variants. However, recent advances in cancer genomics have prompted developments of somatic variant calling approaches that do not require normal ploidy assumptions and can be used for analysis of samples with chromosomal malformations or circulating tumor cells. The latter situation is essentially identical to viral or bacterial resequencing scenarios. As a result of these developments the current set of variant callers appropriate for microbial studies includes updated versions of “legacy” tools (FreeBayes (opens new window) and mutect2 (a part of GATK (opens new window)) as well as dedicated packages (Breseq (opens new window), SNVer (opens new window), and lofreq (opens new window)). To assess the applicability of these tools we first considered factors related to their long-term sustainability, such as the health of the codebase as indicated by the number of code commits, contributors and releases as well as the number of citations. After initial testing we settled on three callers: FreeBayes, mutect2, and lofreq (Breseq’s new “polymorphism mode” has been in experimental state at the time of testing. SNVer is no longer actively maintained). FreeBayes contains a mode specifically designed for finding sites with continuous allele frequencies; Mutect2 features a so called mitochondrial mode, and lofreq was specifically designed for microbial sequence analysis.

# Benchmarking callers: lofreq is the best choice

Our goal was to identify variants in mixtures of multiple haplotypes sequenced at very high coverage. Such dataset are typical in modern bacterial and viral genomic studies. In addition, we are seeking to be able to detect variants with frequencies around the NGS detection threshold of ~ 1% (Salk et al. 2018 (opens new window)). In order to achieve this goal we selected a test dataset, which is distinct from data used in recent method comparisons (Bush et al. 2019 (opens new window); Yoshimura et al. 2019 (opens new window)). These data originate from a duplex sequencing experiment recently performed by our group (Mei et al. 2019 (opens new window)). In this dataset a population of E. coli cells transformed with pBR322 plasmid is maintained in a turbidostat culture for an extensive period of time. Adaptive changes accumulated within the plasmid are then revealed with duplex sequencing (Schmitt et al. 2012 (opens new window)). Duplex sequencing allows identification of variants at very low frequencies. This is achieved by first tagging both ends of DNA fragments to be sequenced with unique barcodes and subjecting them to paired-end sequencing. After sequencing read pairs containing identical barcodes are assembled into families. This procedure allows to reliably separate errors introduced during library preparation and/or sequencing (present in some but not all members of a read family) from true variants (present in all members of a read family derived from both strands).

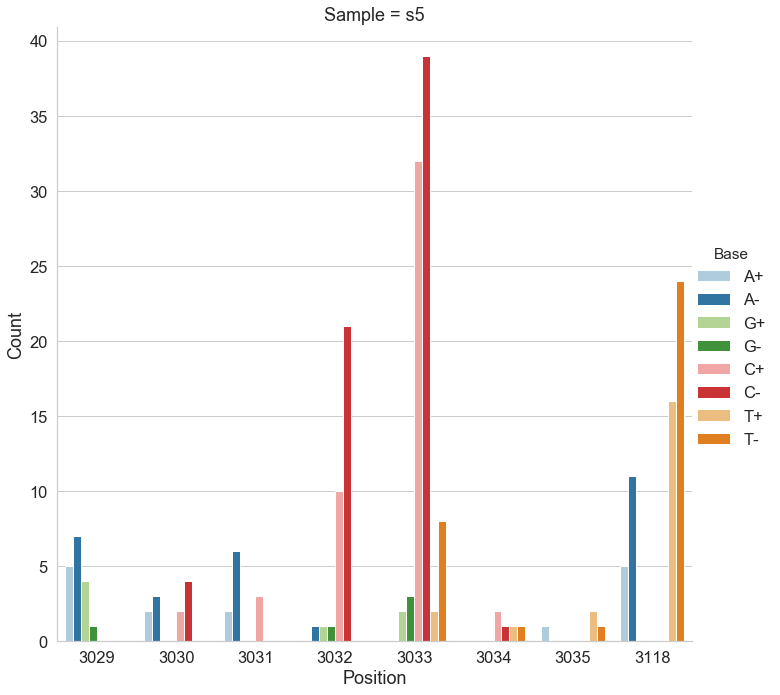

For the following analysis we selected two data points from Mei et al. 2019 (opens new window): one corresponding to the beginning of the experiment (s0) and the other to the end (s5). The first sample is expected to be nearly clonal with no variation, while the latter contains a number of adaptive changes with frequencies around 1%. We aligned duplex consensus sequences (DCS) against the pBR322. We then walked through read alignments to produce counts of non-reference bases at each position (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Counts of alternative bases at eight variable locations within pBR322.

Because all differences identified this way are derived from DCS reads they are a reasonable approximation for a “true” set of variants. s0 and s5 contained 38 and 78 variable sites with at least two alternative counts, respectively (among 4,361 bases on pBR322) of which 27 were shared. We then turned our attention to the set of sites that were determined by Mei et al. to be under positive selection (sites 3,029, 3,030, 3,031, 3,032, 3,033, 3,034, 3,035, 3,118). Changes at these sites increase the number of plasmid genomes per cell. Sample s0 does not contain alternative bases at any of these sites. Results of the application of the three variant callers with different parameter settings (shown in Table 2) are summarized in Fig. 2.

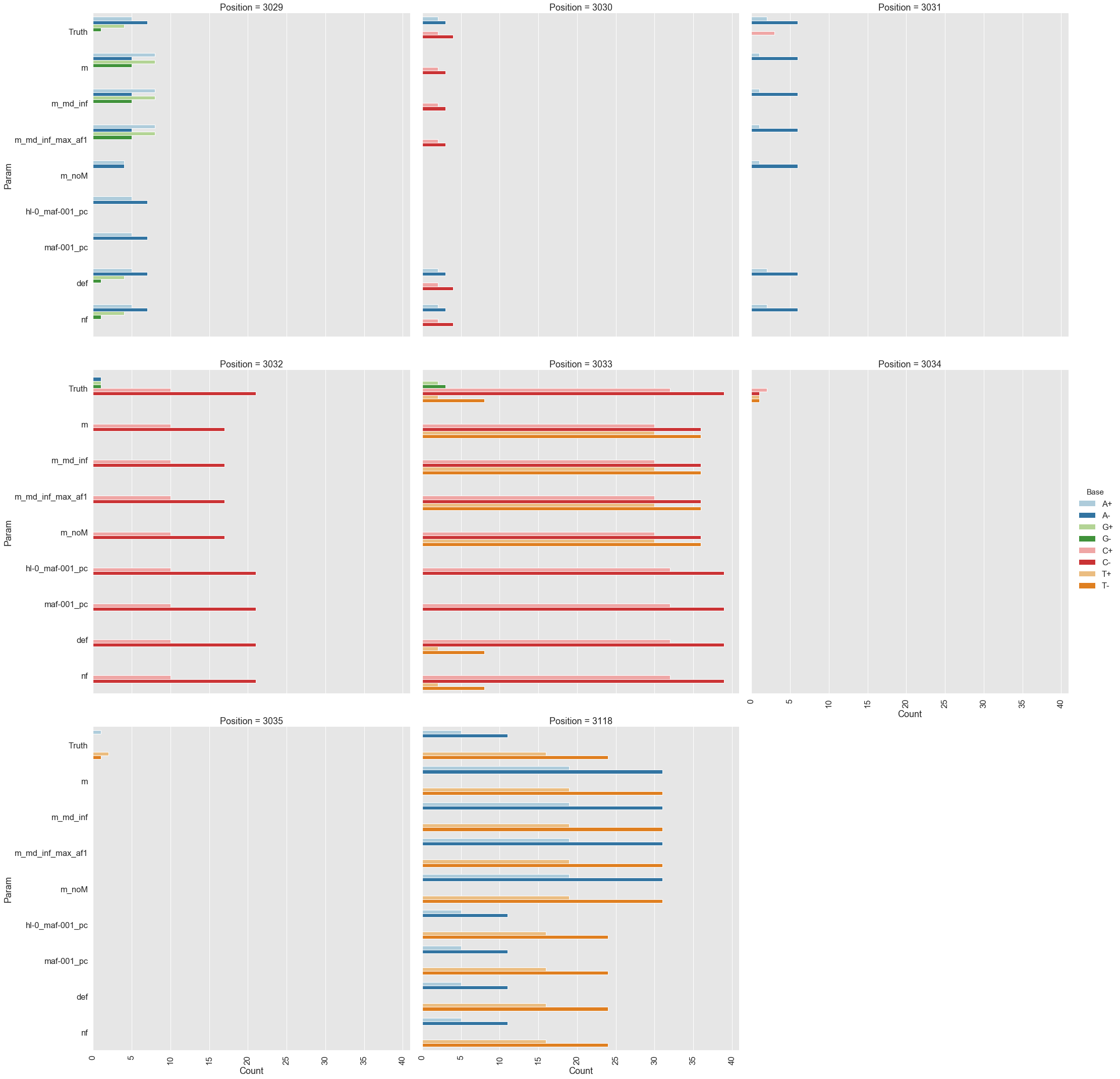

Figure 2. Calls made by mutect2, freebayes, and lofreq. For explanation of x-axis labels see Table 2.

The lofreq performed the best followed by mutect2 and FreeBayes (contrast "Truth" with "nf" and "def" in Fig. 2). The main disadvantage of mutect2 is in its handling of multiallelic sites (e.g., 3,033 and 3,118) where multiple alternative bases exist. At these sites mutect2 outputs alternative counts for only one of the variants (the one with highest counts; this is why at site 3,118 A and T counts are identical). Given these results we decided to use lofreq for the main analysis of the data.

Table 2. Command line options for each caller.

| Caller | Command line | Figure 2 label |

|---|---|---|

mutect2 | --mitochondria-mode true | m |

mutect2 | default | m_noM |

mutect2 | --mitochondria-mode true --f1r2-max-depth 1000000 | m_md_inf |

mutect2 | --mitochondria-mode true --f1r2-max-depth 1000000 -max-af 1 | m_md_inf_max_af1 |

freebayes | --haplotype-length 0 --min-alternate-fraction 0.001 --min-alternate-count 1 --pooled-continuous --ploidy 1 | hl-0_maf-001_pc |

freebayes | -min-alternate-fraction 0.001 --pooled-continuous --ploidy 1 | maf-001_pc |

lofreq | --no-default-filter | nf |

lofreq | default | def |

# Galaxy workflows

lofreq is used in two galaxy workflows described in this section. Illumina data currently available for SARS-CoV-2 consists of paired- and single-end datasets. We use two similar yet distinct workflows to analysis these datasets.

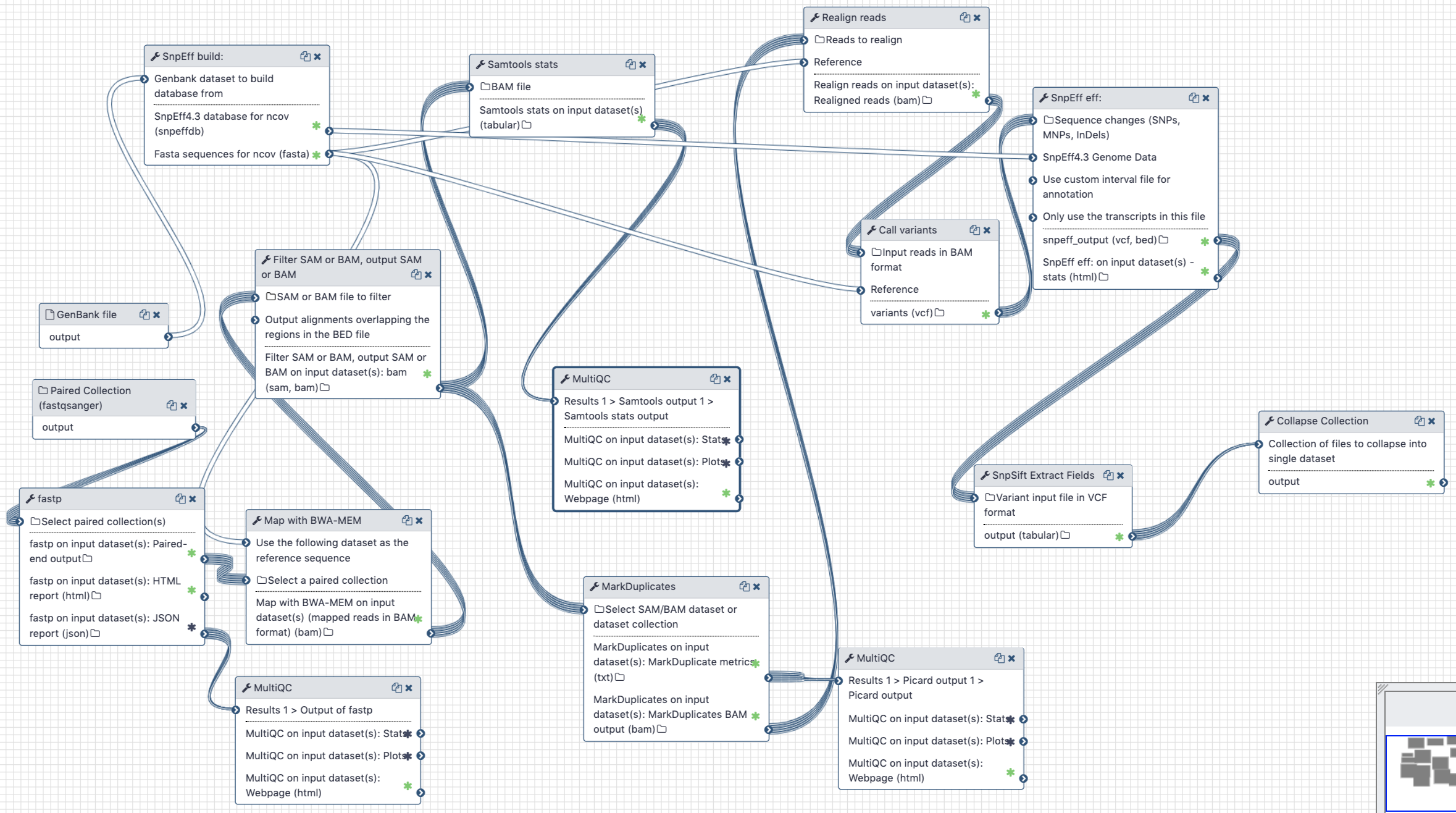

# Analysis of Illumina Paired End data

Figure 3. Workflow for the analysis of paired-end Illumina reads

# Inputs:

- GenBank file for the reference COVID-19 genome (opens new window). The GenBank record is used by

snpeffto generate a database for variant annotation. - Downloaded paired-end reads in fastq format as a paired dataset collection. Reads can be downloaded using Galaxy's wrapper for

fasterq-dumplocated in "Get data" tool section.

# Steps:

- Map all reads against COVID-19 reference NC_045512.2 (opens new window) using

bwa mem - Filter reads with mapping quality of at least 20, that were mapped as proper pairs

- Mark duplicate reads with

picard markduplicates - Perform realignments using

lofreq viterbi - Call variants using

lofreq call - Annotate variants using

snpeffagainst database created from NC_045512.2 GenBank file - Convert VCFs into tab delimited dataset

# Outputs

A tab-delimited table of variants described in Table 2 below.

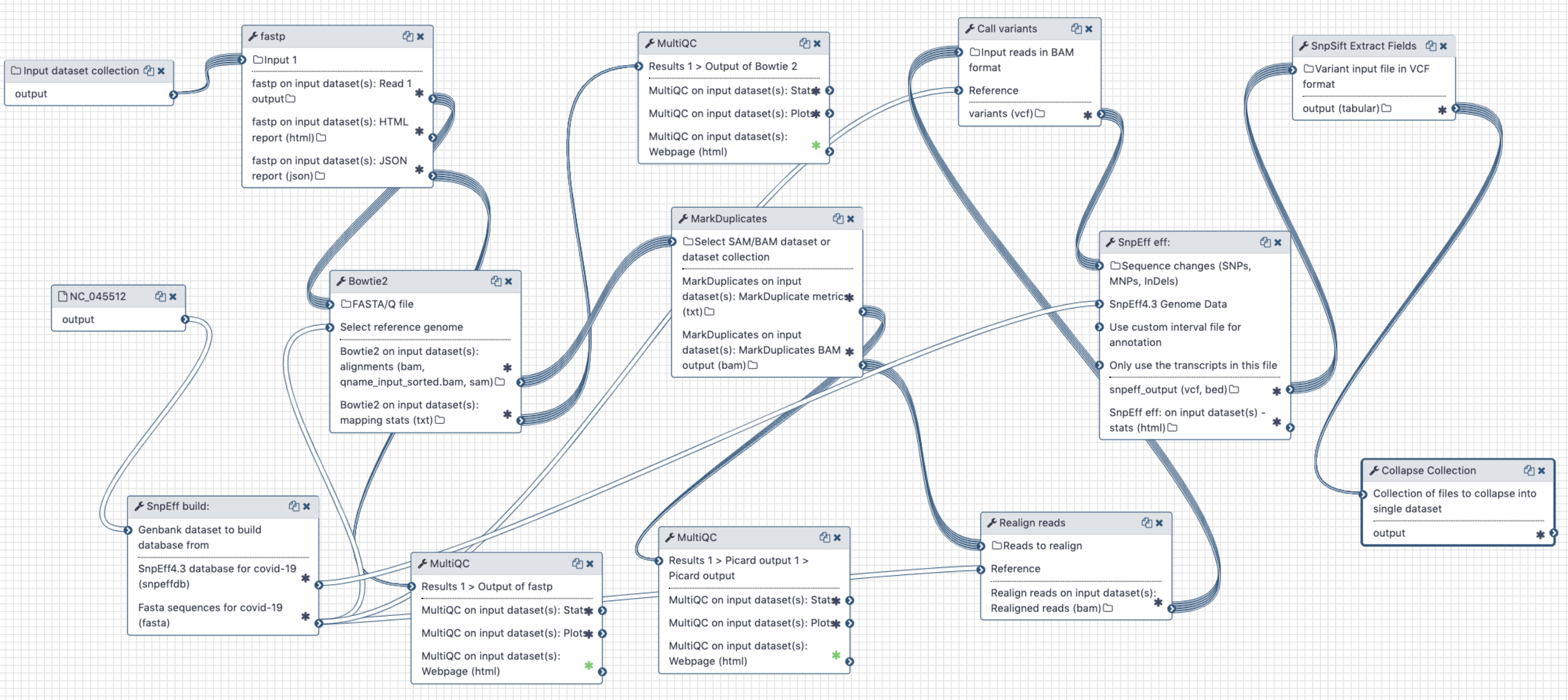

# Analysis of Illumina Single End data

Figure 4. Workflow for the analysis of single-end Illumina reads < 100 bp

Figure 4. Workflow for the analysis of single-end Illumina reads < 100 bp

# Inputs:

- GenBank file for the reference COVID-19 genome (opens new window). The GenBank record is used by

snpeffto generate a database for variant annotation. - Downloaded paired-end reads in fastq format as a dataset collection. Reads can be downloaded using Galaxy's wrapper for

fasterq-dumplocated in "Get data" tool section.

# Steps:

- Map all reads against COVID-19 reference NC_045512.2 (opens new window) using

bowtie2(because all SE datasets we have seen so far contain short, 75 bp, reads) - Filter reads with mapping quality of at least 20

- Mark duplicate reads with

picard markduplicates - Perform realignments using

lofreq viterbi - Call variants using

lofreq call - Annotate variants using

snpeffagainst database created from NC_045512.2 GenBank file - Convert VCFs into tab delimited dataset

# Output

After running both workflows the data is combined into a single dataset (variant_list.tsv and smaller dataset filtered at alternative allele frequency of 5% and above variant_list.05.tsv).

These result datasets have the following structure:

Table 3. Output of PE and SE workflows described above. Here, most fields names are descriptive. SB = the Phred-scaled probability of strand bias as calculated by lofreq (opens new window) (0 = no strand bias); DP4 = strand-specific depth for reference and alternate allele observations (Forward reference, reverse reference, forward alternate, reverse alternate).

| Sample | CHROM | POS | REF | ALT | DP | AF | SB | DP4 | IMPACT | FUNCLASS | EFFECT | GENE | CODON | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | SRR10903401 | NC_045512 | 1409 | C | T | 124 | 0.040323 | 1 | 66,53,2,3 | MODERATE | MISSENSE | NON_SYNONYMOUS_CODING | orf1ab | Cat/Tat |

| 1 | SRR10903401 | NC_045512 | 1821 | G | A | 95 | 0.094737 | 0 | 49,37,5,4 | MODERATE | MISSENSE | NON_SYNONYMOUS_CODING | orf1ab | gGt/gAt |

| 2 | SRR10903401 | NC_045512 | 1895 | G | A | 107 | 0.037383 | 0 | 51,52,2,2 | MODERATE | MISSENSE | NON_SYNONYMOUS_CODING | orf1ab | Gta/Ata |

| 3 | SRR10903401 | NC_045512 | 2407 | G | T | 122 | 0.024590 | 0 | 57,62,1,2 | MODERATE | MISSENSE | NON_SYNONYMOUS_CODING | orf1ab | aaG/aaT |

| 4 | SRR10903401 | NC_045512 | 3379 | A | G | 121 | 0.024793 | 0 | 56,62,1,2 | LOW | SILENT | SYNONYMOUS_CODING | orf1ab | gtA/gtG |

# Jupyter notebook

Upon completion of single- and paired-end analysis workflows and combining their results into a single file this file is loaded into a

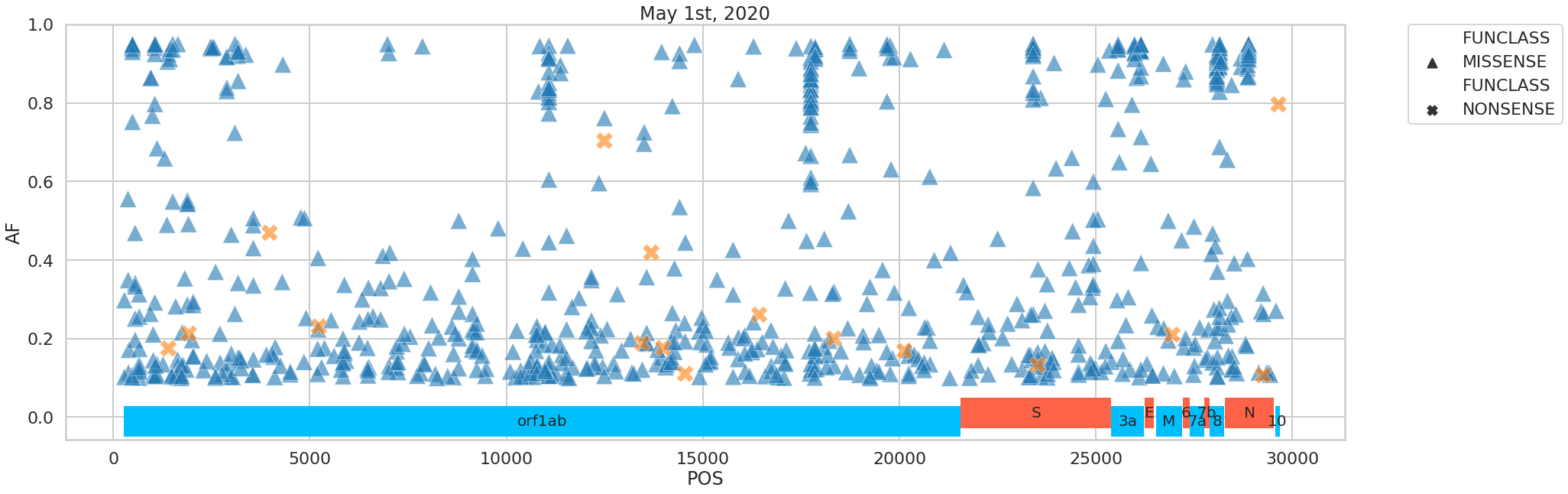

The variants we identified were distributed across the SARS-CoV-2 genome in the following way:

Figure 5. Distribution of variants across the viral genome.

# Galaxy histories

Galaxy histories corresponding to all analyses performed so far are listed in Table 1. The history used for aggregating results and launching jupyter notebook is here →

# BioConda

Tools used in this analysis are also available from BioConda:

| Name | Link |

|---|---|

bwa | |

samtools | |

lofreq | |

snpeff | |

snpsift | |

porechop | |

filtlong | |

minimap2 | |

bowtie2 |